Aviation produces around 2.5% of global carbon dioxide emissions, but its total climate impact runs higher when accounting for nitrogen oxides, contrails, and water vapor. As pressure mounts to decarbonize, hydrogen-electric propulsion has moved from theory to reality. In 2026, demonstration flights will test whether this technology can transform commercial aviation.

The Market Momentum

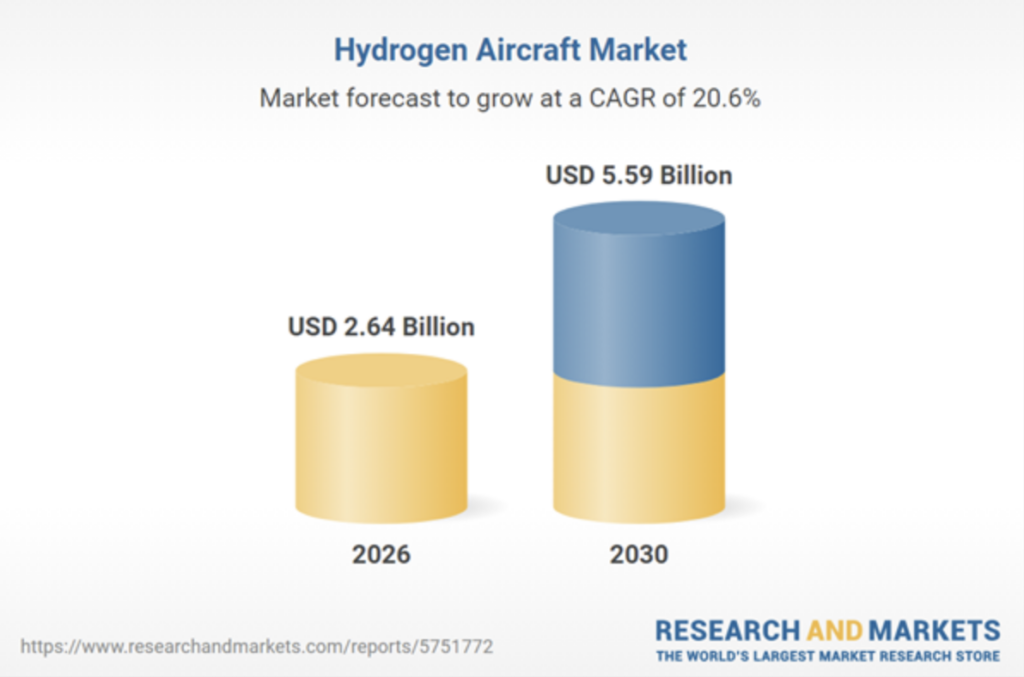

The hydrogen aircraft market reached $2.16 billion in 2025 and projects to hit $2.64 billion by 2026 with a compound annual growth rate of 22.1%. This reflects tangible progress in hydrogen propulsion methods, onboard storage systems, fuel cell development, and electric motor technology for aviation.

Major airlines including American, United, Alaska, IAG, and Airbus have committed investment capital. ZeroAvia alone holds over 2,000 pre-orders for its hydrogen-electric powertrains. The EU Innovation Fund recently awarded ZeroAvia a €21.4 million grant for hydrogen infrastructure development in Norway.

KLM’s 2026 Demonstration Flight

Dutch airline KLM partnered with British-American startup ZeroAvia to conduct a liquid hydrogen demonstration flight in 2026 between two European airports. The flight will utilize ZeroAvia’s ZA2000 hydrogen-electric engine designed for large regional turboprops.

ZeroAvia’s engines use fuel cells to generate electricity, which powers electric motors turning propellers. The only emission is low-temperature water vapor. Studies estimate up to 90% reduction in climate impact compared with kerosene-fueled flights when accounting for both CO2 and non-CO2 emissions.

The ZA2000 presents new challenges. While ZeroAvia has flown a 19-seat Dornier 228 dozens of times using gaseous hydrogen, liquid hydrogen requires cryogenic storage below -252.87°C. ZeroAvia must develop tanks capable of withstanding tens of thousands of flight cycles under commercial aviation safety standards.

How Hydrogen Flight Works

| Component | Function | Key Challenge |

| Liquid hydrogen tanks | Fuel storage at -253°C | Maintaining cryogenic temps |

| Fuel cell stacks | Convert H2 to electricity | Aerospace weight-to-power ratio |

| Electric motors | Drive propellers | Power density for commercial use |

| Battery systems | Peak power during takeoff | Integration with fuel cells |

Hydrogen packs three times the energy of jet fuel by weight. The problem lies in volume – hydrogen requires heavy tanks for storage either as compressed gas or cryogenic liquid.

Retrofitting a propeller plane with fuel cells and liquid hydrogen tanks would result in nearly 90% reduction in lifecycle emissions compared to the original aircraft, assuming renewable electricity generates the hydrogen.

ZeroAvia’s Commercial Timeline

| Year | Aircraft Size | Range | Engine | Status |

| 2026 | 10-20 seats | 300 NM | ZA600 | Certification underway |

| 2027-2028 | 40-80 seats | 700 NM | ZA2000 | Commercial sales planned |

| 2030 | 100 seats | 1000 NM | ZA2000RJ | Development phase |

| 2033 | 100-200 seats | 1500 NM | ZA10000 | Concept stage |

ZeroAvia has submitted plans for its ZA600 engine to aviation authorities for certification. Advanced ground tests in the US and UK for the ZA2000 system have been completed. Both the UK Civil Aviation Authority and US Federal Aviation Administration are working with ZeroAvia on certification programs.

Switching to hydrogen-electric propulsion delivers 40% operational cost savings compared to conventional turboprops, according to ZeroAvia’s analysis. Lower fuel costs, reduced maintenance, and extended airframe life all contribute to improved economics.

ZEROAVIA

Norway’s Hydrogen Network

ZeroAvia’s EU grant funds hydrogen refueling infrastructure at 15 airports across Norway, establishing what would become the world’s largest network of zero-emission commercial flights. The project will retrofit 15 Cessna Caravan aircraft to operate on ZA600 engines, with operations expected by 2028.

Norway’s geography makes it ideal for demonstrating hydrogen aviation. The country has numerous regional routes, abundant renewable electricity for green hydrogen production, and government support for emission reduction. The ODIN project aims to validate technical performance and economic viability.

The Airbus Reality Check

While startups push toward 2026 demonstrations, Airbus delayed its ZEROe program. The European aerospace giant initially promised a hydrogen-powered commercial airliner by 2035 but recently pushed the timeline by five to ten years, potentially into the 2040s.

Airbus cited slower-than-anticipated progress on key enablers: renewable hydrogen production at scale, technology maturity, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructure development. The company cut its ZEROe budget by 25% and canceled plans to flight test a fuel cell powertrain on its A380 demonstrator in 2026.

CEO Guillaume Faury worried the program could become a “Concorde with hydrogen” – technically impressive but commercially unviable. The company has spent over $1.7 billion on hydrogen aircraft development.

Despite the delay, Airbus committed to developing a hydrogen fuel cell-powered aircraft carrying up to 100 passengers over 1,000 nautical miles. The revised design features four propellers, each powered by its own fuel cell stack. Complete propulsion system testing is scheduled for 2027.

Why Hydrogen Beats Batteries

Battery-electric aircraft face fundamental physics problems. Current battery technology can’t power planes beyond a few hundred kilometers. Long flights over 4,000 kilometers constituted just 6% of flights departing European airports in 2020 but accounted for over half of total flight emissions.

Hydrogen-electric technology targets the emissions-heavy long routes that batteries can’t serve. Henri Werij, head of aerospace engineering at TU Delft, estimates liquid hydrogen-powered planes could travel up to 4,000 kilometers using current technology – sufficient for most regional and many mainline routes.

For very small aircraft on short routes, batteries work. For everything else, hydrogen offers the only realistic zero-emission alternative to sustainable aviation fuels, which face limited availability and higher costs while still producing emissions during flight.

Infrastructure Challenges

Hydrogen aviation requires complete ecosystem transformation. Airports need hydrogen production facilities, cryogenic storage systems, and specialized refueling equipment. Energy providers must scale renewable electricity generation. Regulators must develop certification standards. Maintenance organizations need training for hydrogen-specific procedures.

These challenges explain Airbus’s caution and ZeroAvia’s focused approach. The startup concentrates on regional aircraft where infrastructure requirements are manageable. Airbus faces the harder problem of mainstream commercial aviation requiring hydrogen availability at hundreds of airports worldwide.

The Airbus Hydrogen Hubs at Airports program currently partners with over 220 airports plus numerous energy providers and airlines to address production, storage, and distribution questions.

The 2026 Inflection Point

KLM and ZeroAvia’s planned demonstration flight represents more than a technology milestone. It tests whether the complete system – aircraft, fuel production, storage, refueling, maintenance, and operations – can function together under real-world conditions.

The flight will occur under full regulatory oversight with safety standards matching conventional aviation. Unlike experimental test programs, this demonstration aims to prove hydrogen-electric aircraft can operate within existing aviation frameworks.

For scientists, 2026 offers empirical data on critical questions:

- How do cryogenic hydrogen systems perform through complete flight cycles?

- What are the actual operational costs?

- How do pilots and ground crews adapt to hydrogen procedures?

- What unexpected challenges emerge when theory meets practice?

Two Paths Forward

Hydrogen aviation in 2026 exists between startup optimism and established industry caution. Companies like ZeroAvia push aggressively toward demonstration flights. Giants like Airbus acknowledge hydrogen’s necessity while tempering timelines based on ecosystem realities.

Both approaches have merit. Aviation needs bold pioneers willing to take risks. It also needs established manufacturers ensuring safety, reliability, and commercial viability at scale. The industry’s hydrogen future likely depends on both paths succeeding.

The hydrogen aircraft market’s projected growth to $5.59 billion by 2030 reflects industry conviction that this technology will play a significant role in aviation’s decarbonization. Whether that conviction proves justified depends heavily on what happens in 2026.

The Questions That Matter

Can liquid hydrogen storage systems meet aviation’s safety requirements? Will fuel cell stacks achieve the power-to-weight ratios necessary for larger aircraft? How will airlines and airports adapt operations? Can the economics work without massive subsidies?

These aren’t just technical questions. They determine whether aviation can meaningfully decarbonize or remains dependent on fossil fuels for decades. The answers begin arriving in 2026 when demonstration flights transition hydrogen aviation from laboratory to sky.